Static Malware Analysis: Beginner’s Guide

Beginner-friendly guide to static malware analysis: exploring PE structure, imports, entropy, and early IOC detection with tools like Floss, PEView, and PEStudio.

Introduction to Static Malware Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide

Malware analysis is one of the most exciting areas in cybersecurity. It’s the process of examining malicious software to understand its behavior, capabilities, and impact. Broadly, analysis can be divided into static analysis (examining a file without executing it) and dynamic analysis (observing it while it runs in a sandboxed environment).

In this post, we’ll focus on static malware analysis — what it is, why it matters, and how to start using simple tools to uncover malicious intent.

What Is Static Analysis?

Static analysis involves inspecting a file without executing it. The goal is to learn about the program’s structure, imports, strings, and potential malicious functionality.

Why it’s useful:

- Safe: no need to run the malware.

- Quick: can reveal key IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) immediately.

- Foundation: prepares you for deeper dynamic or reverse engineering work.

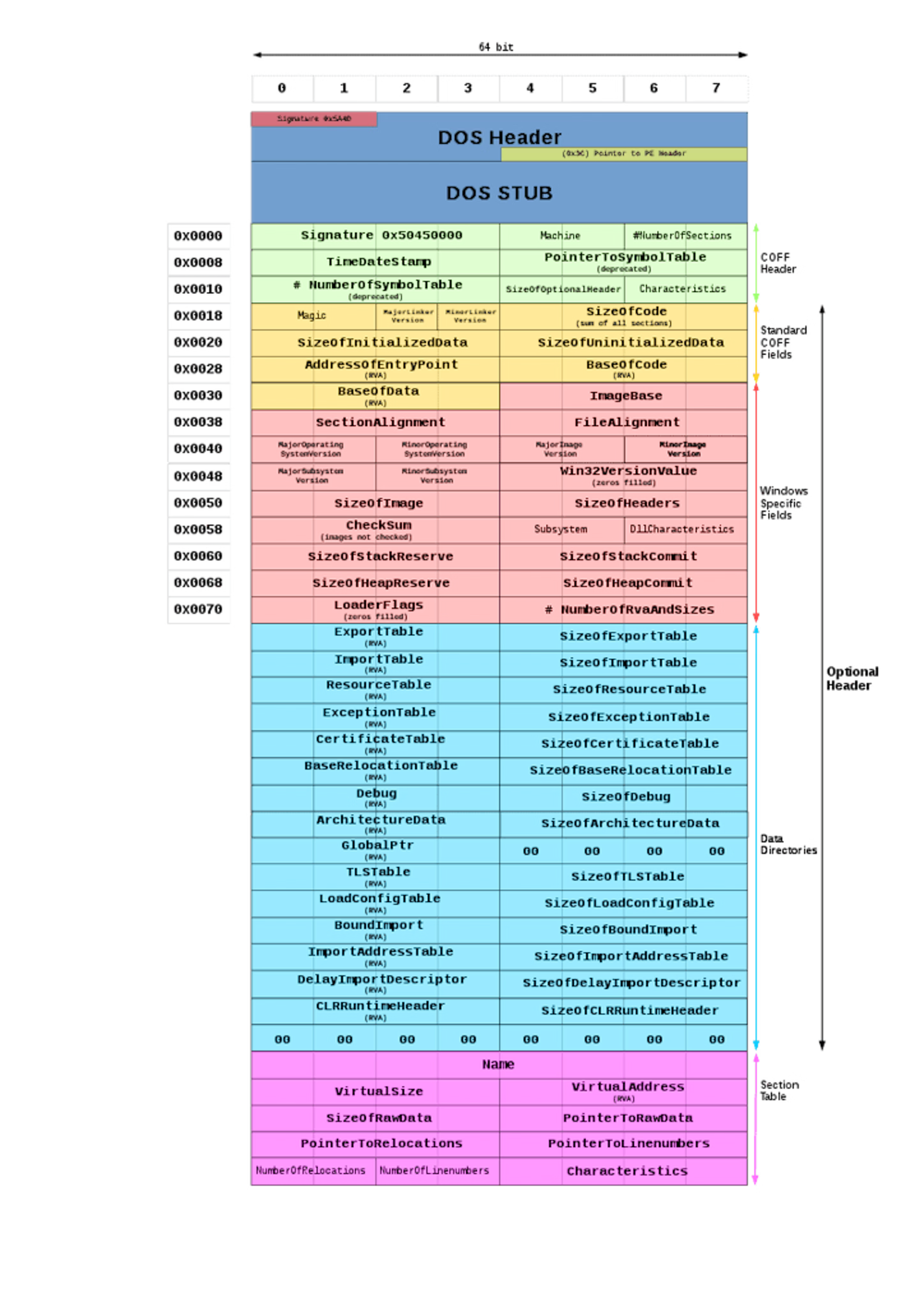

Understanding Windows PE Files

Most Windows malware comes as a Portable Executable (PE) file — the standard format for

Most Windows malware comes as a Portable Executable (PE) file — the standard format for .exe and .dll files.

A PE file has several key parts:

- Headers – metadata about the file, such as compiler info and timestamps.

- .text – the actual executable code.

- .rdata – read-only data, such as API imports.

- .data – global variables and runtime data.

- .rsrc – resources like icons, images, or embedded payloads.

- .reloc – relocation information for memory loading.

📌 Suspicious clues often hide in unusual sections, oversized resources, or unexpected overlays.

Key Indicators to Look For

When performing static analysis, pay attention to:

- Entropy

- Measures randomness.

- Normal executables: ~5–7.5.

-

7.5: likely packed or encrypted.

- <5: often padded or compressed.

- Strings

- Extracted plain-text values.

- Look for URLs, IP addresses, registry keys, file paths, suspicious commands.

- Imports / Exports

- APIs like

CreateRemoteThread,VirtualAlloc,WriteProcessMemorycan indicate injection or persistence. - Many imports hidden or missing → possible packing.

- APIs like

- Resources

- Large or unusual resource files may contain embedded executables, icons, or payloads.

- Overlays

- Extra data appended after the legitimate PE structure — often where attackers hide payloads.

- Compiler Info / Timestamps

- Suspicious if timestamp is far in the past (e.g., 1992) or inconsistent.

- Legitimate compilers leave consistent metadata.

Tools for Static Analysis

Here are some beginner-friendly tools you can use:

- PEStudio

- Flags suspicious indicators (red/yellow markers).

- Extracts imports, strings, resources, and checks against VirusTotal.

- Great first stop for quick triage.

- PEView

- Lets you dig deeper into PE headers and sections.

- Useful for spotting packed binaries (tiny raw size vs huge virtual size).

- FLOSS (FireEye)

- Extracts obfuscated and decoded strings.

- Helps uncover hidden URLs or commands.

- VirusTotal

- Aggregates results from dozens of AV engines.

- Good for a quick sanity check.

Detecting Packers & Obfuscation

Attackers often compress or encrypt malware with a packer like UPX.

Signs of packing:

- High entropy in the

.textsection. - Section names like

UPX0orUPX1. - Very small “raw data size” but large “virtual size” in PEView.

📌 If you suspect packing, you may need to unpack the binary before deeper analysis.

Practical Workflow Example

Here’s a simple workflow to analyze a suspicious binary:

- Open in PEStudio

- Check indicators, imports, strings, and VirusTotal report.

- Check entropy and sections

- Look for unusually high values or abnormal sections.

- Run FLOSS

- Extract plain and obfuscated strings for IOCs.

- Open in PEView

- Compare raw vs virtual sizes to detect packing.

- Document findings

- Record suspicious APIs, extracted IOCs (domains, IPs, hashes), and packing signs.

Even without executing the file, you now have a profile of its behavior.

Sample Static Analysis of WannaCry Malware

Sample Overview

- File Name:

Ransomware.wannacry.exe - File Size:

3636KB - File Type:

.exe - Compile Timestamp:

2010/11/20 Sat 09:03:08 UTC - Entropy:

The overall file entropy was calculated as 7.964, which is higher than the expected range for standard, unpacked Windows executables. This suggests that the file is packed or encrypted.- MD5:

db349b97c37d22f5ea1d1841e3c89eb4

- MD5:

- SHA1:

e889544aff85ffaf8b0d0da705105dee7c97fe26 - SHA256:

24D004A104D4D54034DBCFFC2A4B19A11F39008A575AA614EA04703480B1022C - VirusTotal

Static Analysis

Examine file metadata

Extract readable text from Binary.

Tool used: Floss (Full Results)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

FLARE FLOSS RESULTS (version v3.1.0-0-gdb9af41)

+------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| file path | Desktop\Ransomware.wannacry.exe.malz |

| identified language | unknown |

| extracted strings | |

| static strings | 45337 (284069 characters) |

| language strings | 0 ( 0 characters) |

| stack strings | 15 |

| tight strings | 0 |

| decoded strings | 6 |

+------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

──────────────────────────────

FLOSS STATIC STRINGS (45337)

──────────────────────────────

+-------------------------------------+

| FLOSS STATIC STRINGS: ASCII (45038) |

+-------------------------------------+

!This program cannot be run in DOS mode.

Rich

.text

`.rdata

@.data

.rsrc

_^][

SUVW

_^][

WUhx

We can see a repetition of the above lines from lines 325, which suggests that this might be a packed binary.

We see the presence of a URL:

http://www.iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com

According to VirusTotal, this is malicious.

We see some references to cryptography

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Microsoft Enhanced RSA and AES Cryptographic Provider

CryptGenKey

CryptDecrypt

CryptEncrypt

CryptDestroyKey

CryptImportKey

CryptAcquireContextA

cmd.exe /c "%s"

We can also see some IPC$ shares and a list of file extensions, probably the ones which will be encrypted by WannaCry:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

\172.16.99.5\IPC$

Windows 2000 2195

Windows 2000 5.0

\192.168.56.20\IPC$

kernel32.dll

WanaCrypt0r

Software\

.der

.pfx

.key

.crt

.csr

.p12

.pem

.odt

.ott

.sxw

.stw

.uot

.3ds

.max

.3dm

.ods

.ots

.sxc

.stc

.dif

.slk

.wb2

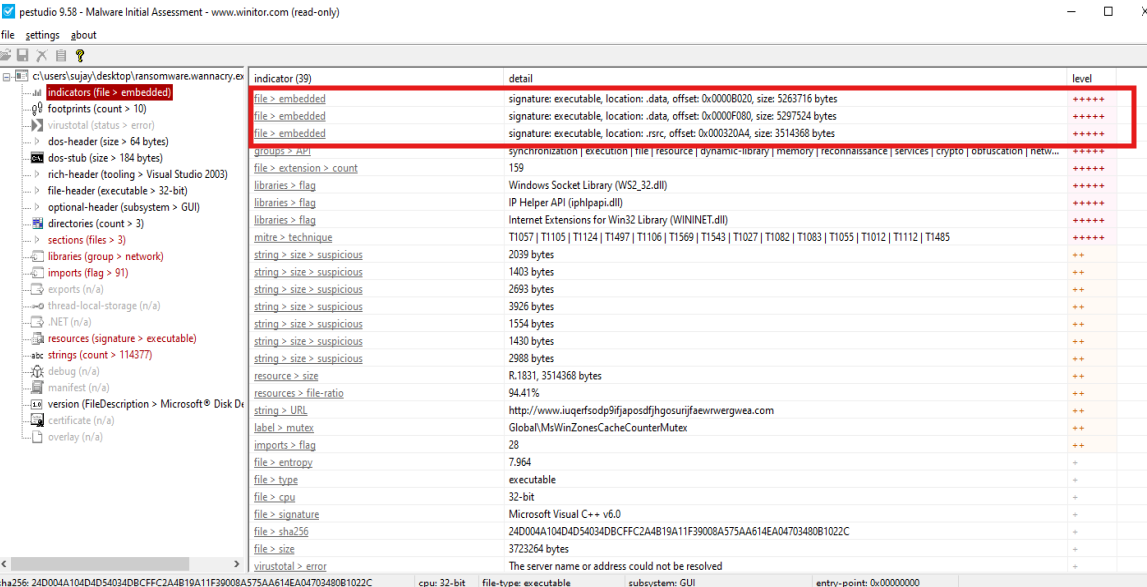

File Characteristics

Tool used: PEStudio

We can see that there are three binaries within the file.

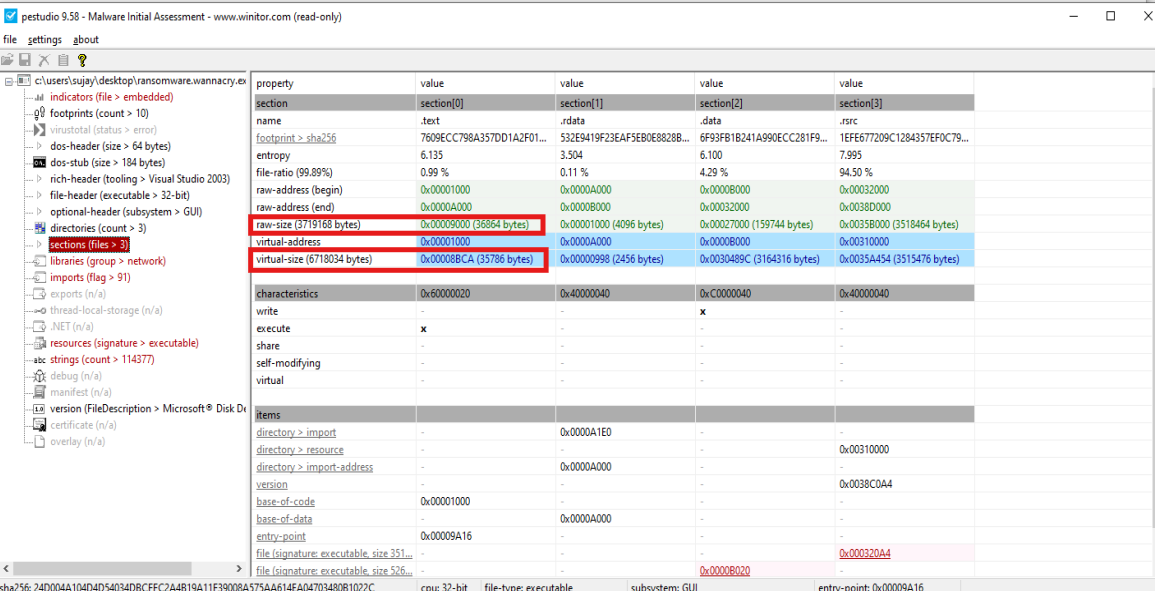

Looking at the raw size and virtual size, there isn’t much difference, so we can determine that the binary is not packed:

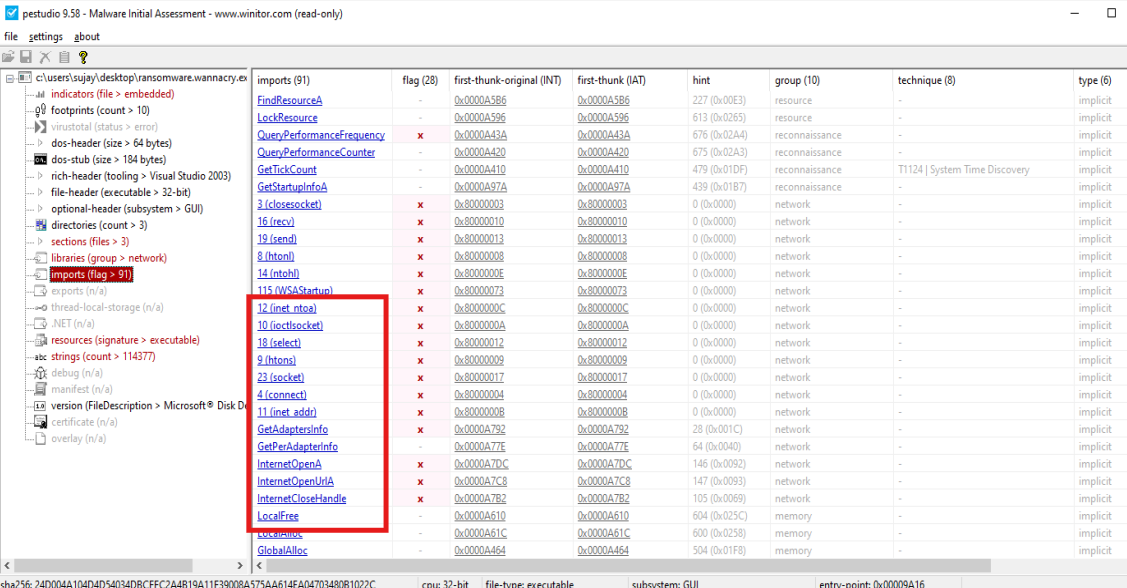

Some suspicious imports, including opening a URL from the internet.

Conclusion

Static analysis is the first step in malware research. By carefully examining binaries, you can uncover suspicious indicators, extract IOCs, and decide whether deeper dynamic analysis is necessary.

It’s safe, efficient, and an essential skill for anyone moving toward malware analysis, threat research, or DFIR.

In my next post, I’ll dive into dynamic analysis — running malware in a controlled sandbox to observe its real behavior.

Written by Sujay Sundar Raj — Security Engineer & Malware Analysis Enthusiast.